And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

(The Second Coming, William Butler Yeats)

(an old article that I found actual nowadays, in 2025 – this is a translation of my article, written in Romanian, December 20, 2016)

The Twitches of the Electric Eye

The seasonal consumerist whims of one part of the world are spiced with moments of emotional hangover in the retina worn out by the horrors from the other part of the world. The abandoned supermarket cart in an American parking lot arrogantly echoes the rusty remains of cars used in the desperate flight of the hopeless among the ruins of Aleppo. In fact, the human monstrosity virtually consumed in Western teenagers’ video games brands itself live into the nerves, skin, and cries of the dying in Syria and beyond.

Aleppo is not only the signature of Obama’s failure on the certificate of his Nobel Peace Prize, but also the bleeding wound of humanity—one that might compel Fukuyama to revise his thesis on the end of history. History ends when its subject capitulates to its own toxic genetic fountain—one that no educational or transhumanist utopia can alter. Anywhere, anytime, the Cain-virus within us lies in wait to fuel our fratricidal violence. And that’s because we were first infected with the virus of deicidal violence.

When horror from there becomes horror here, the heavy eyelids of Western toil and entertainment snap open in wonder and fear. The year 2016 was a more hurried trickle of the horrors of 2015. The flood of breaking news staining not just the screens but also the world’s streets competed with the flashes of celebrity culture that feed the therapeutic dreams of consumers resisting the ever-growing temptation to escape into the reality of psychotropics. Over 700 overdose deaths in the first 11 months of 2016 in British Columbia—Canada (with a population just slightly larger than Bucharest’s)—became a macabre chorus accompanying the voice of millions of souls torn from their bodies—abortions, murders, diseases, wars. The world grows ever more unbreathable. And as a parent looking around with both eyes, you feel a pang in your chest seeing what waves of horror await your children in the years to come.

The Mutant Re-Birth

2016 brought an increased surge of migratory waves that shattered the fragile goodwill and hope in humanity—brutalized serenities, arrogant lies, hysterics, and forced steps into the barracks of fear. The modern human keeps trying to deny the obvious, to project convenient guilt, to edit the language of horrors in the hope they’ll lose their ontological referent. He self-encapsulates in false penances just as much as he lays hands on ritual scapegoats, hoping it’s all just an accident of brain chemistry, global warming, socio-economic or gender inequality, shoe size or underwear color—a divine whim with no chance of real existence. The surprise is that this astonishing capacity for self-deception is powerless in the face of a reality that greedily tears with iron teeth into the frail body of what remains of optimism and innocence.

The secular man, living under the shadow of a bizarre mix of voluntary consumerism and activist Marxist utopias, finds himself speaking more and more about apocalypse, fear, and metaphysical dread.

A striking example of this apocalyptic fear is the persistence with which William Butler Yeats’ poem, written near the time of the First World War, circulated across 2016 social media:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the center cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

(William Butler Yeats, The Second Coming, January 1919)

The vortex of history brings us back to the place the world departed from 2000 years ago. (The first verse speaks of a spiral—gyre—that leads us to the last two verses, which depict the mutant rebirth at Bethlehem—a distorted, inverted Messiah: the Antichrist). Because creation can no longer hear the Creator (The falcon cannot hear the falconer), the world has lost its center (the center cannot hold), and anarchy spreads across the wrinkled face of the earth (mere anarchy is loosed upon the world). The absence of conviction allows for the rise of the most violent ideologies (The best lack all conviction, while the worst/ Are full of passionate intensity), a premonition of the value-vortex of postmodern relativism and nihilism—glorified in universities, media, and culture—which drives youth into the arms of all sorts of militant extremisms. Over the grave-like silence of the past twenty centuries rises the shadow of a beast seeking birth—as a false messianic imitation—at Bethlehem.

The birth of Christ at Bethlehem in the context of a maniacal killer like Herod speaks volumes: even God begins with what is vulnerable, frail, unstable, and under threat from the “good” as conceived and executed by the human mind. We certainly cannot envy the times in which the Son of God was born, hunted by a diabolical beast like Herod, who manipulated society on his fingers, killed his own family out of paranoia while feigning benevolence and charity, and so on. Yet our times seem increasingly to resemble that same crossroads of eternity.

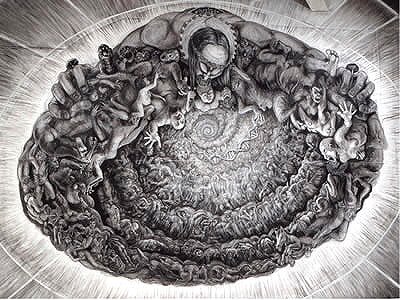

Our great problem today is that we’ve amputated our sense of the transcendent, anesthetized our organ for converting suffering into self-becoming, and locked ourselves in the asylum of utopian, odorless, and colorless ideas. The ecstasy of autistic pleasures has now melted into a dark and intoxicating spasm of a mutant rebirth—a Martian Jesus, a Santa Claus, a replicated Mephistopheles present everywhere, lost souls, failed DNA strands, all caught in the song of a new world’s creation—a humanity, a destiny—a creation that can only unfold through destruction, violence, degenerative life, and agonizing death.

Beyond the Apocalypse

In March 1996, Umberto Eco wrote a letter to his friend Carlo Maria Martini titled “The Secular Obsession with a New Apocalypse” (included in their dialogue collection What Do Those Who Do Not Believe Believe In?, Polirom, 2011, Romanian version; the English version is Belief or Nonbelief?, published in 2000 at Arcade Publishing). Eco rightly observes:

Today we live (even in the distracted, absent-minded way that mass media have taught us) our own terrors of the end; we could even say we live them in the spirit of bibamus, edamus, cras moriemur—celebrating the end of ideologies and solidarity in the whirlpool of an irresponsible “consumerism.” Thus, each of us plays with the fantasy of the Apocalypse while simultaneously trying to exorcise it; the more we exorcise it, the more our unconscious fear of this fantasy grows, one we project in the form of a bloody spectacle in hopes that it will thereby become unreal. Yet the strength of phantoms lies precisely in their unreality.

[…] I dare say that concern for the end times is today more characteristic of the secular world than of the Christian one. In other words, the Christian world treats it as a subject of meditation but behaves as if its projection into a timeless dimension were justified; the secular world pretends to ignore it, yet is genuinely obsessed with it. This is not a paradoxical situation, for it merely repeats everything that happened in the first millennium. (In What Do Those Who Do Not Believe Believe?, pp. 13–14)

Eco concludes his meditation on the secular obsession with the apocalypse by intuiting the Christian interpretive key to Revelation:

Christianity invented history, and the modern Antichrist denounces it as a disease. Perhaps secular historicism understood this history as infinitely perfectible, so that tomorrow would always surpass today, constantly and without exception, and within that same history, God himself would transform—educate and enrich himself, so to speak. But this ideology does not belong to the entire secular world, which has also seen the madness and decline strewn across history; there is nonetheless a distinctively Christian vision of history whenever that path is traveled under the sign of Hope. Thus, only by learning to judge history and its horrors are we fundamentally Christian—when we speak of tragic optimism, with Mounier, or of the pessimism of reason and the optimism of the will, with Gramsci. (What Do Those Who Do Not Believe Believe In?, pp. 15–16)

Leave a reply to Caleb Cheruiyot Cancel reply